We had just walked in to our house with the mail when Mommy began sobbing uncontrollably. The letter she was reading congratulated my brother on his new summer job.

But he was dead.

My brother, Marlo Terry, was 21 when he was shot in the back after opening a bedroom door at a friend’s house. He was

trying to help his friend escape two gunmen, one of whom had an ongoing feud with my brother’s friend.

Marlo had applied for a summer gig at UPS months before; getting that acceptance letter a week after he was buried in spring 1994 was one more reminder of what we had lost.

Although my brother died in Memphis, not Chicago, my mom’s experience of having to bury her own child is one she shares with too many families here in the Windy City.

More than 500 people were killed last year in Chicago; another 400-some were slain the year before.

Over the past semester, I and my fellow journalism students at Columbia College Chicago reviewed these nearly 1,000 cases to learn what we could about the effect homicide has on friends, relatives, neighbors, co-workers and so many others. Then we set out to tell some of those stories.

This journey triggered memories dating back more than 20 years.

After learning from one of my Columbia classmates about the Rodriguez family watching a video of 24-year-old Harry dancing not long before he was killed in 2011, I remembered my brother performing a popular 1990s dance called Gangsta Walking before our home camera.

When I read that Rodney Stewart had bought a bus ticket and planned to leave Chicago just a few days before he was shot to death in 2012, I couldn’t help but think about my brother’s plan to drive back to college the day before he was killed.

The bouts of depression and insomnia Tony McCoy Jr.’s mother has suffered since her son’s murder two years ago reminded me all too well of my mother’s health issues.

Each story that a classmate documented prompted another memory, some sad and some good, like our big brother-little sister time.

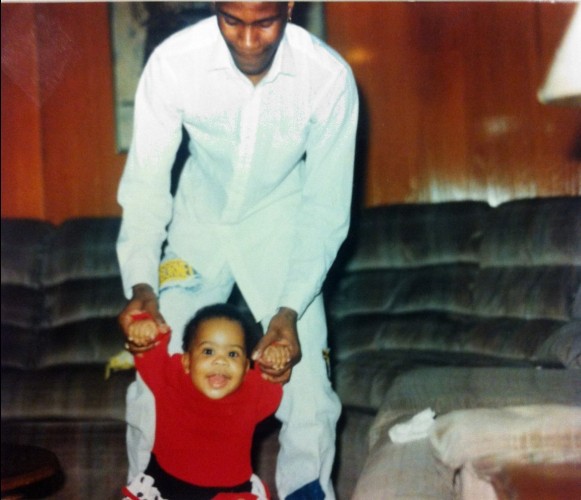

While we were 18 years apart, we were close. My mommy was surprised one day after returning from work to discover Marlo had just spent hours teaching me how to walk.

One morning, I excitedly walked upstairs to his room to wake him up, so he could drive me to day care. When he didn’t immediately crawl out of bed, I climbed in with him and laid there until Mommy called for us.

Each time he had to go back to college, I ran from the back door to the front door to watch him drive away and cried, because he’d be gone for a while.

The last time I cried, he was gone forever. I was just 4.

His killers were caught, and both are serving life sentences in prison.

That’s not true for many of the Chicago homicides my classmates and I investigated this spring. No arrests have been made in most of those cases, leaving families across Chicago and beyond to pick up the pieces and wonder if justice will be served.

I listened to my mommy as she burst into tears that day so long ago clutching yet another reminder of Marlo’s presence – and absence. I didn’t really understand why she was crying, so I just sat on her lap and cried with her

I now better understand her sorrow – and the grief too many other families here in Chicago must endure.

When my mommy cried, I cried.

This story is part of a week-long series about homicides in Chicago. ChicagoTalks, a news outlet operated by Columbia College’s Journalism Department, undertook a semester-long investigation of the topic funded with a grant from The Chicago Community Trust. ChicagoTalks is publishing additional stories throughout the week. If you have questions or comments, please e-mail project editor Suzanne McBride at smcbride@colum.edu.

Read more from this series:

- Argument over basketball game takes parents’ only child

- Family seeks answers after 8th grader’s murder

- Family, friends of murdered Uptown businesswoman say they have been left in the dark

- Killer on the line

- Lonely anniversary

- For some, the grieving never ends

- Families say silence the norm after Chicago homicides

- Homicide victim’s mother sees progress in Englewood

- Giving up on justice

- Families question support after loved ones’ killings

- Unsolved homicide not forgotten

- Final call to a friend

Be First to Comment